: Could not find asset snippets/file_domain.liquid/assets/img/top/loading.png)

江戸時代中期に中国から煎茶の文化と共に舶来し、その後日本独自の発展を遂げながら現代まで連綿と続いてきた花籠の歴史。その中でも、黒河内真衣子が特に心を奪われたのがオリジナリティあふれる創作で日本における竹籠文化を芸術の域へと押し上げたパイオニア的作家、飯塚琅玕斎の作品でした。2023年春夏から秋冬コレクションまでの1年間を通して黒河内の制作の着想源となった琅玕斎の作品と日本の竹籠文化について、さまざまな竹籠のコレクションを所有し、国内外で展示の企画、プロモーションを行う斎藤正光さんにお話を伺います。

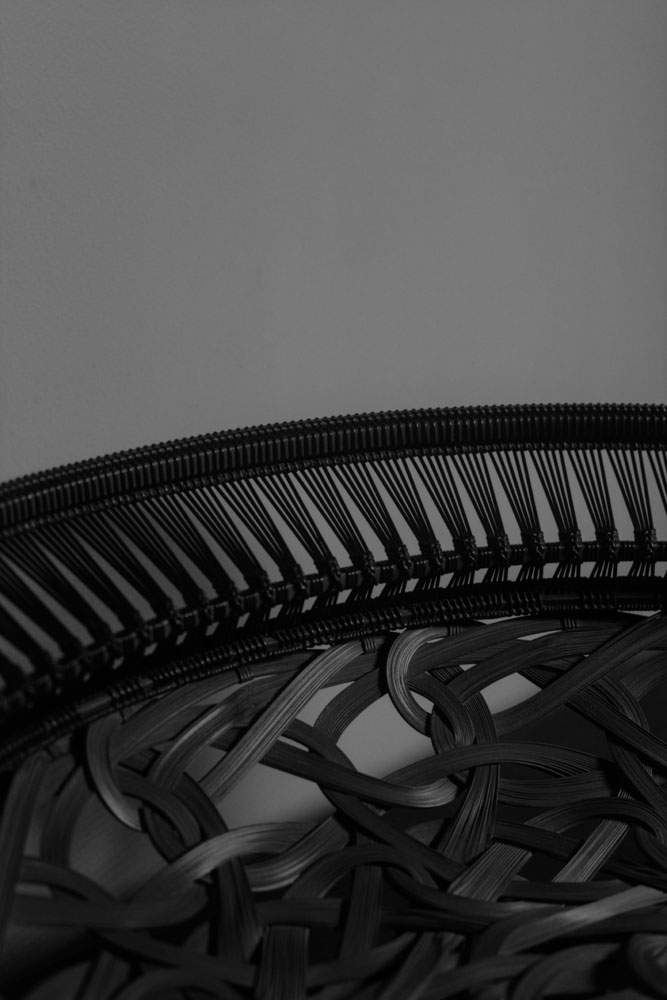

「飯塚琅玕斎について知るにはとっておきの作品があります。『国香』という盛籃です。1939年に琅玕斎が得意とした束ね編みという技法を用いて作られました。国の香りという名前の通り日本の国花である菊がモチーフになっています。菊の花びらが広がるように綿密に作り込まれたこの作品は、スケッチなどの設計図は無く、手の感覚と想像力だけを頼りに編み上げられています。こうした複雑かつ繊細な籠を編み上げる琅玕斎の創造性と技術は、唯一無二といえるでしょう。束ね編みという技法は、細い竹を束ねて編んでいることに由来しています。例えば、ご祝儀袋などに使われる水引を想像していただくと分かりやすいと思います。こうした日本の伝統的な意匠を竹籠に昇華することは、琅玕斎の得意とするところのひとつです。そして、竹ひごを撓め、竹なりの美しい曲線で生まれる造形も竹籠の醍醐味です。竹の作品は、金属やガラスのように一度溶かして形を作るのではなく、完成形をイメージしながら、素材を仕込むところからはじまります。時には、竹藪や竹林から伐採し、それらを切って薄さや厚さ、太さや細さを調整していくのです。この作品は、整備された竹林から伐採された質の良い竹を使用し、竹を縦に割ることでうまれる細くてしなやかな竹が用いられています。節が曲線の頂点にくると折れてしまうので、そこまで計算しながら繊細なバランスを見極めて編んでいるのが分かります。そうして自在には曲がりにくい素材の特徴と自身の制作意図と折り合いをつけていく。『折り合う美術』『征服しない美術』という考え方は実に日本的だと感じます。」

「時代によってさまざまな編みの表現が生まれた竹籠。最初は、中国から煎茶の道具として日本に広がり、その後、煎茶文化が盛り上がるにつれて増えた需要に応えるように日本でも茶室で使われる竹籠、いわゆる花籠がつくられるようになりました。当時は『唐物写し』と呼ばれ、唐の花籠を模したデザインがほとんどでした。しかし、そこに日本人独自の解釈を取り入れ、さらには、煎茶の道具としてだけでなくオブジェという概念とともに花籠を制作した先駆者が琅玕斎でした。琅玕斎が独自の感覚で編み上げた花籠は、やがて芸術作品として評価されるようになり、煎茶や花道の道具に止まらない竹籠の岐路を見出したのです。興味深いことに、そうした芸術性の高い作品であっても花籠としての用途や機能は付随している。琅玕斎は『花が入ってもよし、入らぬもよし』と自作の籠について述べています。」

竹という素材が作り出す独自の曲線から生まれる籠の数々。実用性と装飾性がバランス良く共存するデザイン。そして、民具を芸術へと昇華させるきっかけとなる日常へ向けられた丁寧な目線。そこには、女性の日常や体のシルエット、そしてその曲線美に寄り添うMame Kurogouchiが強く共鳴したいくつもの物語がありました。

The history of flower baskets travels back to the mid-Edo period in Japan, having been imported from China along with the culture of sencha tea, continuing its own transformation in Japan uninterrupted. Among its rich history, Maiko Kurogouchi was particularly fascinated by the works of Rokansai Iizuka, a pioneering artist who elevated bamboo basket culture in Japan to the realm of art with his original creations. The 2023 collection throughout the year for both Spring/Summer to Autumn/Winter, were inspired by the works of Rokansai and bamboo basket culture. We sat together with Mr. Masamitsu Saito, a collector, exhibition curator and promoter of bamboo baskets to learn about its surrounding culture.

To deepen our understanding about Rokansai Iizuka, there is a special piece of work, a large bowl called ‘Kokkou’※. Created in 1939, Rokansai used a technique he was skilled in called bundled-plait, the motif being the chrysanthemum, the national flower of Japan. The meticulously crafted work resembles the spread of chrysanthemum petals, relying solely on the artist's imagination and hand-weaving sense, with no blueprints such as sketches. This creativity and skill of Rokansai, who weaves complex and delicate baskets, is unparalleled. This technique of bundled-plait is derived from the thin bamboo being bundled and woven. Take for example, the ‘mizuhiki’, a decorative art form of knot-tying made from beautiful ornamental cords, used for gift envelopes. One of Rokansai’s strengths is to sublimate such traditional Japanese designs into bamboo baskets. Bending the strips of bamboo, it creates a beautiful curved shape, the epitome of bamboo baskets. Unlike metal or glass where materials are melted to create shapes, for bamboo baskets one must visualize the final piece, and it all begins with the preparation of materials. At times, one must retrieve bamboo from bamboo groves or forests, and cut them to adjust the thickness and thinness. The ‘Kokkou’ uses high-quality bamboo, cut from well-maintained bamboo groves, and uses thin, flexible bamboo created by splitting the bamboo lengthwise. The knot is carefully calculated and woven in a delicate balance, as if the knot reaches the top of the curve it may break. In this way, Rokansai compromises and combines the bamboo's characteristics and his own production intention in harmony. This idea of ‘Art that Compromises’ and ‘Art though not conquer’ is truly Japanese.” ※Kokkou (国香)= Country + Scent

Bamboo baskets have been woven into various expressions over time. Initially, bamboo baskets spread from China to Japan as utensils for sencha tea. As sencha culture flourished in Japan, in order to meet the growing demand, bamboo baskets, so-called flower baskets used in tea rooms began to be made. At the time, most were called ‘Karamono Utsushi’, where most designs imitated the Chinese flower baskets. However, Rokansai incorporated a unique Japanese interpretation, pioneering the creation of flower baskets not only as a utensil for sencha, but also as objects. Flower baskets woven with his own uniqueness soon came to be appreciated as works of art, finding crossroads for bamboo baskets that go beyond sencha and Kado, a traditional Japanese ikebana tools. Interestingly, even such works of high artistic quality are accompanied by its use and function as flower baskets. Rokansai mentions his own baskets as ‘Able to contain flowers, or not contain flowers.’

Bamboo baskets made from bamboo and its unique curves, with a design that balances practicality and decorativeness. And sublimating folk craft into artwork by having a careful perspective towards everyday life. The many stories shared with Mame Kurogouchi strongly resonated with her consideration towards women’s daily lives, silhouettes, and beauty in curves.

Photography: Yuichiro Noda / Words & Edit: Runa Anzai (kontakt) /Translation: Shimon Miyamoto