: Could not find asset snippets/file_domain.liquid/assets/img/top/loading.png)

“くずし=変容

連続的に姿をかえ、表情をかえてゆくかたち

そこに日本的な特色は見出せないだろうか。

原型を抽象し

さらに抽象して

表現を強化し

強調してゆこうとする西欧の傾向に対して

原型の集中的強さを

崩し、乱し、暈して、その余韻をもって拡散しようとする傾斜。

そんなふうにはいえないだろうか。”

「日本のかたち forms in japan」(1963年/美術出版社)

その一文で手を止めた。

日々のかたちのリサーチの中で書と再会し、子供の頃ぶりに書道をしてみた。お勧めされた高野切第三種をお手本に墨をすり、水を足し、筆を走らせる。流れるような連綿が理解できなくとも毎日書き続けていると、ふと、文字と自分の身体が溶け合うような感覚が生まれた。言葉の意味がじんわりと身体に染み込むような経験だった。初心者の私でも、かつての書道家たちがこうやって文字を崩していったのではないかと感じるほどに、興味深い体験だった。この「溶け合う」感覚から生まれたのが、今シーズンの墨流しのファブリックだ。水の上で墨が滲み合い生まれる偶然のかたちはとても興味深く、この技法を継承する工場は今では京都でも数えるほどしかない。

“Kuzushi = transformation

A form that continuously shifts its shape and expression

Could this not be seen as a uniquely Japanese characteristic?

While Western aesthetics often abstract the original, then abstract it further to intensify and emphasise expression,

there seems to be a Japanese inclination to deconstruct, distort, blur—

and allow the essence to diffuse through lingering impressions.

Could we not describe it this way?”

— Forms in Japan, Bijutsu Shuppansha (1963)

This passage made me stop in my tracks.

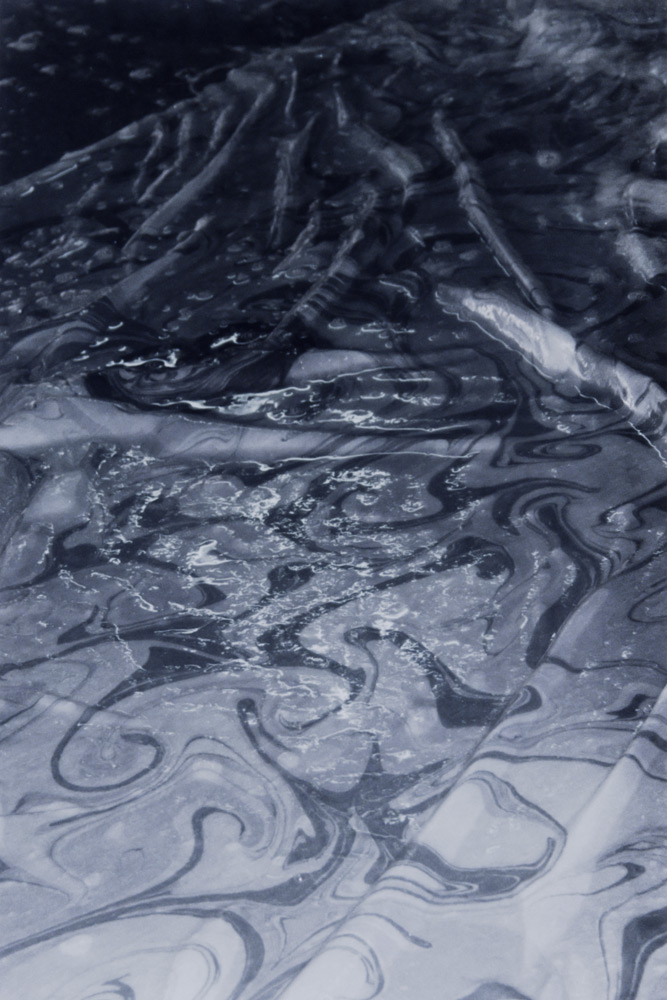

While researching “Katachi” or forms in my daily life, I reencountered shodo—Japanese calligraphy—and tried it again for the first time since childhood. Following a recommendation, I used the Koyagire 3rd fragments, a fragment of a handwritten manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū (Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems), as my model; grinding ink, adding water, and moving the brush across the paper. Even though I couldn’t fully grasp the flowing beauty of the continuous strokes—something gradually began to shift as I practiced each day. At some point, I felt a deep connection, as if the characters and my body were melting into one. It was an experience where the meaning of the words slowly soaked into me, both physically and emotionally. As a beginner, I sensed that perhaps this is how calligraphers of the past deconstructed and transformed characters. It was an incredibly engaging experience. This feeling of "melting together" inspired this season’s suminagashi fabric. The unpredictable forms created by the dispersion of ink on water are endlessly fascinating. Today, only a handful of workshops in Kyoto still carry on this traditional technique.

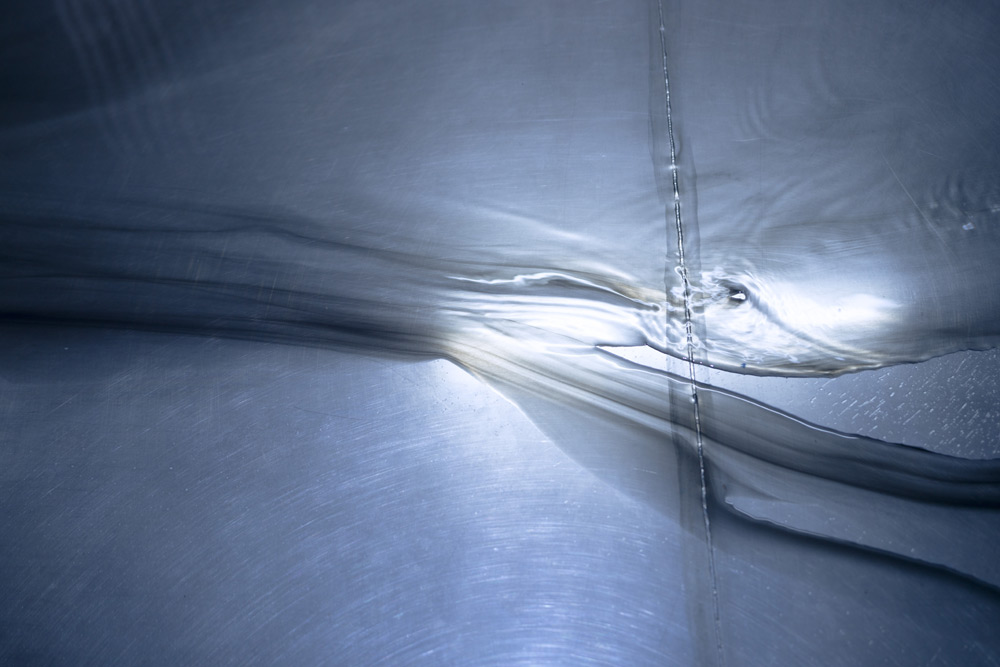

染色工場の真ん中に銀色の大きな水槽のようなバットが置かれ、中の液体が反射してきらきらしていた。

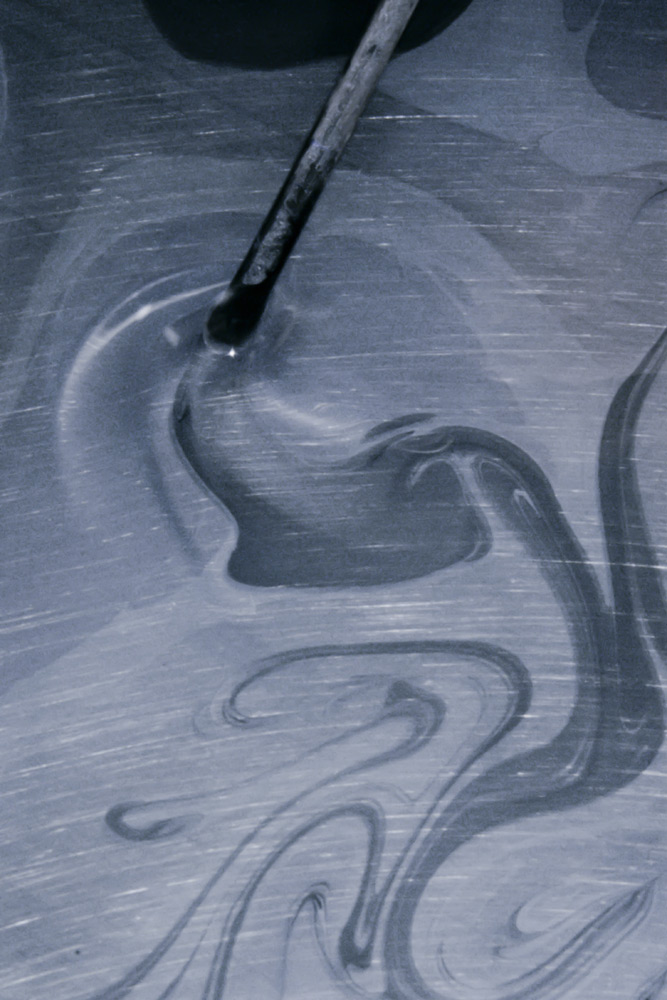

職人さんがとろとろの液体にぽつんと黒色を垂らす。

ゆっくりと細く柄が流れ、また次を垂らす。今度はその景色を菜箸でなぞることで形がさらに歪んでいく。それを繰り返していくことで複雑なマーブル模様が浮かび上がる。

とろとろの液体は水とのりを混ぜたもので、その配合バランスは、作り出す柄の「ゆらぎ」のおもしろさと量産の可能性を突き詰めたものであり、職人さんが考えた特別な配合だ。

私の描いたドローイングを見ながら職人さんが手際よくリズミカルに描いていく。動かしている手は滑らかだが、柄が歪まぬうちに仕上げなくてはいけない。時間との勝負だ。

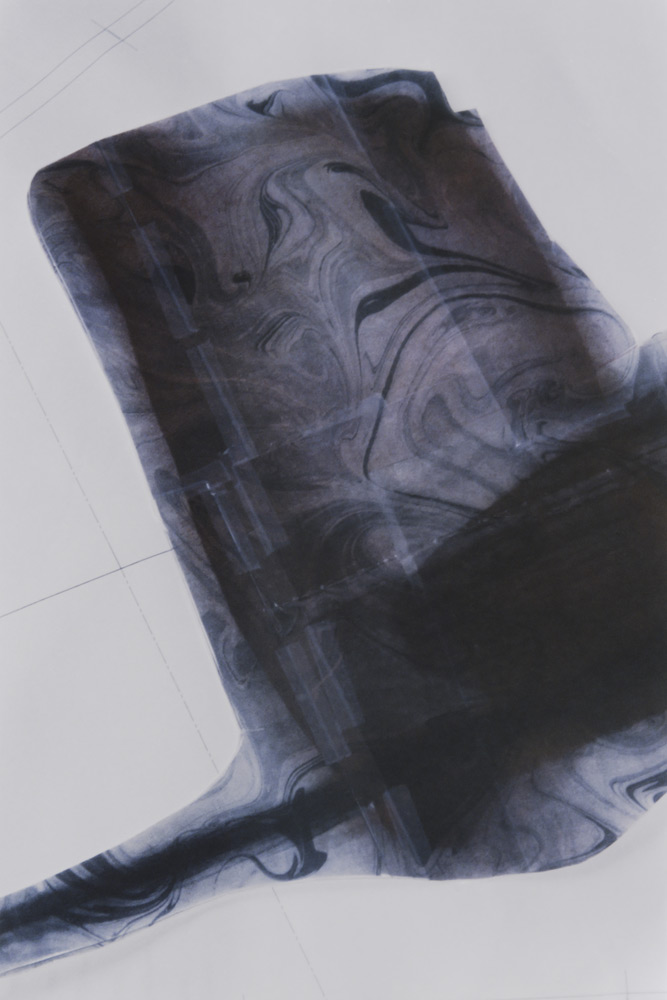

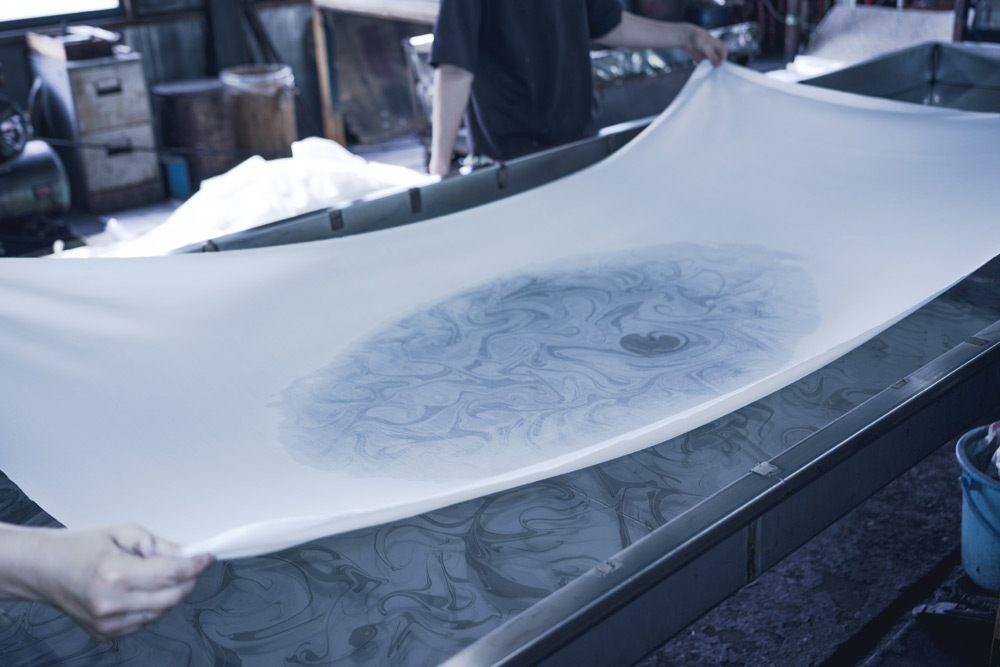

生地の両端を持ち、息を揃えてその水面に生地を降ろして柄を写しとって行く。タイミングがずれると空気が入ってしまう。息を止めて見守った。

生地が水面に触れると中心からふわっと柄が滲み出し、じわぁと端々まで水面をトレースした。

In the centre of the dyeing workshop sat a large, silver vat, almost like a water tank. The surface of the thick liquid inside shimmered as it reflected the light.

A craftsman dropped a small dot of black ink into the viscous liquid.

The colour slowly stretched and flowed into a delicate pattern. Another drop followed.

This time, the craftsman traced the spreading ink with a pair of long chopsticks, distorting the shape further. Repeating this process, a complex marble-like pattern began to emerge.

The viscous liquid is a blend of water and starch. Its unique balance had been perfected by the artisan—not only to allow for mesmerising organic "fluctuations" in the pattern, but also to ensure the technique could be repeated for production. It was a special formula, crafted through experience and experimentation.

The artisan moved with rhythm and precision, occasionally glancing at my original drawing.

Their hands flowed smoothly, but the design had to be completed before it warped. It was a race against time.

They lifted the fabric by its edges and, in perfect coordination, gently lowered it onto the liquid surface to capture the pattern. If the timing was off, air bubbles could form. I held my breath and watched.

As soon as the fabric touched the surface, the pattern began to bloom softly from the centre, gradually spreading outward and tracing every edge of the cloth.

平安時代から始まったとされる墨流しは、たまたま川の水面に墨を落としてしまい、その変化するかたちに面白みを感じた王朝貴族の遊びだったとも言われているらしい。曲水の宴をしていたのかもしれない。

長い時間を経て、かたちが変わりながらも守られてきたその技術により、また新たなかたちを生み出せることに喜びを感じながら、時間と共に変容していく水面をずっと見ていた。

Suminagashi, said to have originated in the Heian(8th-12th century) period, is believed to have begun as a playful pastime among court nobles—perhaps when ink was accidentally dropped onto the surface of a river, it captured their imagination. One can easily imagine such moments unfolding during a Kyokusui-no-en, the elegant poetry gatherings by flowing water.

Over the centuries, though its form has changed, the technique has been preserved—passed down through generations. Watching the surface of the water transform, I felt a quiet joy in being able to create something new from this enduring craft.

I found myself simply gazing, absorbed in the ever-changing surface of the water.